It is just a Territorial Dispute…Really??

The traditional narrative

Kashmir, which has boundaries

with Tibet, China, Russia and Afghanistan, has been placed in a pronounced

strategic position. The Kashmir region has gone through a tumultuous history

through its existence as it has passed from ruler to ruler and empire to

empire.

The history of Kashmir is

entwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the adjoining

regions - comprising the areas of Central Asia, South Asia and East Asia. It

denotes a larger area that includes the Indian-administered state of Jammu and

Kashmir (which consists of Jammu, the Kashmir Valley, and Ladakh), the

Pakistan-administered territories of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit–Baltistan, and the

Chinese-administered regions of Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract.

Islamization in Kashmir took

place during 13th to 15th century and led to the eventual decline of the

Kashmir Shaivism in Kashmir. In 1339, Shah Mir became the first Islamic ruler

of Kashmir. For the next five centuries, Islamic rulers governed Kashmir,

including the Mughals, who ruled from 1586 until 1751, and the Afghan Durrani

Empire, which ruled Kashmir until 1819. In 1819, the Sikhs, under Ranjit Singh,

took over Kashmir. In 1846, after the Sikh defeat in the First Anglo-Sikh War,

and upon the purchase of the region from the British, the Raja of Jammu, Gulab

Singh, became the new ruler of Kashmir. The rule of his descendants, under the

protection of the British Crown, lasted until 1947, when the former princely

state became a disputed territory. Kashmir is now administered by three

countries: India, Pakistan, and the People's Republic of China.

The Kashmiris are,

anthropologically, an Indo-Aryan Dardic ethnic group living in or originating

from the Kashmir Valley, located in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir

(J&K). The bulk of Kashmiri people predominantly live in the Kashmir Valley

and also form a majority of the population in the Chenab region's Doda, Ramban

and Kishtwar districts. Smaller populations of Kashmiris also continue to live

in the remaining districts of the state of J&K.

Kashmiri (or Koshur) is spoken

primarily in the Kashmir Valley and Chenab regions of Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. As per the

2001 census of India there were over 5.5 million speakers of Kashmiri in India.Interestingly, people from the

Azad Kashmir (or Pakistan occupied Kashmir) are neither Kashmiris nor do they

speak the Kashmiri language. People from Azad Kashmir are typically related to

the people of northern Punjab in Pakistan, and they mostly speak Punjabi,

Pahari, Gujjari languages. There are very few Kashmiris (the Indo-Aryan Dardic

ethnic group who originally hail from the Kashmir Valley) in Azad Kashmir and

while they still speak Kashmiri but many of their younger generation have

adopted Pahari or Urdu and do not anymore speak Kashmiri. This essentially

means that there remains a linguistic divide between the present day

inhabitants of Pakistan-administered territories of Azad Kashmir and the

inhabitants of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K).

Islam is practically

the singular religion throughout the northern areas of the Indian-administered

state of J&K and Azad Kashmir on the Pakistani side of the 1972 Line of Control,

accounting for more than 99.5% of the population in every single district of

those two areas. On the Indian side of the LOC, Hinduism is the second most

numerous faith and accounts for a majority of the population in the three

southernmost districts of Jammu and in that region as a whole. Followers of the

Tibetan form of Buddhism are a definite majority in the large, but sparsely

populated district of Leh and in Zanskar tahsil in the southern part of Kargil

district. In the state of J&K as a whole, Islam is by far the leading faith

and accounted for close to 75% of the total population by 1981.

The overwhelming majority of

Kashmiris being Muslims, Islamic identity does plays a very important role in

the daily lives of the majority of the Kashmiri people. However, Kashmiris

across the religious divide have for centuries shared cordial and friendly

ties.

As on date, however, the prickly

issue remains the status of the Kashmir Valley, whose inhabitants are divided

between demanding independence or allegiance to Pakistan, with a proportion

opting to remain within India. The key issues that stems from the traditional

narrative on the Kashmir dispute include –

- Demands of the Islamic majority of the inhabitants of

the state of J&K living in the valley are not universally shared by the

minorities living in different areas of the state.§ The Buddhist population of Ladakh has never supported

the cause for either for Kashmir’s independence or accession to Pakistan, nor

has the majority Hindu population of the Jammu region.

- To date, the Government of India has refused to

reconsider the possibility of holding a plebiscite in J&K. Without,

however, holding a plebiscite or referendum it is next to impossible to

determine exactly what proportion of the people support which option.

Pakistan has consistently called

for the issue to be resolved by means of a plebiscite and has blamed India for going

back on its pledge. But although it supports the Kashmiri’s ‘right of

self-determination,’ Pakistan has shied away from accepting the third option as

a possible outcome - a third option being an independent Kashmir with non-allegiance

to either India or Pakistan or China. India,

on the other hand, blames Pakistan for supporting anti India militant groups

which it says are fomenting an Islamist insurgency in Indian Kashmir. This

strengthens the development of the alternative narrative that Kashmir is more

than just a territorial dispute.

The emerging narrative

The emerging narrative is that Kashmir

is definitely more than a territorial and nationality dispute. The disputes

emanates from the very fact that it is situated in the northern part of Indian sub-continent,

and has boundaries with China (Tibet), Russia and Afghanistan, and is thus placed

in a position of significant strategic importance. The Indian state of Jammu

and Kashmir (or J&K in short) is, geographically, a continuation of the

plains of West Pakistan into the mountains (western Himalayas).

A certain section of the

international community feels, and perhaps rightly so, that over period of many

years India and Pakistan have progressively arrived at a tacit agreement for

the settlement of ownership of territories and in all likelihood the ‘Line of

Control’ can be a step to it, and thus the dispute on Kashmir is no longer

about altering its boundaries. It is perhaps not too abstract to infer that the

military and civilian leadership of both countries recognize that the idea of

going to war on Kashmir is no longer realistic. Water (or the lack of it) has now

emerged as more central premise to the Kashmir issue between the two neighbours although

initially it was only a territorial issue, or at best an issue of nationality

for the original inhabitants of this strategic landmass in Asia.

J&K is emerged as a much

prized landmass for both India and Pakistan – essentially to ensure long term

sustainability of both nations by way of securing, controlling and harnessing precious

waters of this prized landmass.

Pakistan’s population has been growing

at an annual growth rate of 2.3 % as compared to India’s 1.3 %. Consequentially,

in the last five decades, Pakistan’s per capita water availability has dropped

from 5,600 to 1,038 cubic metres.

The figure is expected to further fall to 809 cubic metres by 2025, as

estimated by the Pakistan’s Water and Power Development Authority. The country

is fast moving from a water- scarce nation to a water-starved one. Its sole

dependence on the Indus — 70 % of the country’s inhabitants live in the Indus

basin — intensifies its critical water position.

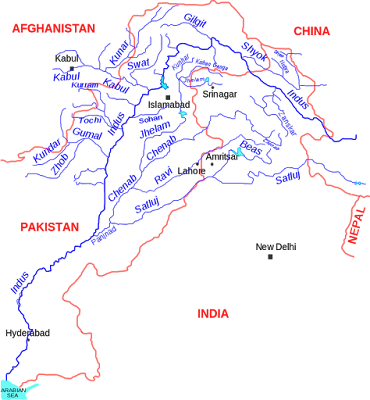

Being an agricultural country, it’s

rivers – Indus, Jhelum and Chenab – are its

sources of life. These three rivers flow into Pakistan from the State of J&K.

Pakistan, readers may kindly note that, is a lower riparian country in the

Indus valley system.

According to a dominant school of

thought in Pakistan both Kashmir and the water flowing from Kashmir into

Pakistan are matters of life and death to Pakistan. The same school of thought

also perceives that without securing sovereignty for Kashmir Pakistan's

sovereignty and security will always be on threat.

What the Green Revolution gave

India and as well as Pakistan — an abundance to export water hungry crops — has

now become unfeasible. Even in the most arid areas, farmers have no alternative

but to irrigate their fields by flooding them. Few have adopted the much more

efficient drip irrigation system, which governments urgently need to subsidize.

Climate change too compounds the water problem. Experts say that climate change

could alter the timing and rate of snow melt, with an initial increase in

annual run-off, followed by a steep decrease as glaciers recede, severely impacting

river flows.

The Riparian Rights

Under riparian law, water is a

public good like the air, sunlight, or wildlife. It is not ‘owned’ by any

government, state or private individual but is rather included as part of the

land over which it falls from the sky or travels along the surface. ‘Riparian rights’

is a system for allocating water among those who possess land along its path. Under

the riparian principle, all landowners whose properties adjoin a body of water

have the right to make reasonable use of it as it flows through or over their

properties. If there is not enough water to satisfy all users, allotments are

generally fixed in proportion to frontage on the water source. These rights

cannot be sold or transferred other than with the adjoining land and only in

reasonable quantities associated with that land. The water cannot be

transferred out of the watershed without due consideration as to the rights of

the downstream riparian landowners.

The Indus Waters Treaty

The Indus Waters

Treaty (IWT, or Treaty), a water-distribution treaty between India and

Pakistan, mediated by the World Bank (then knows as the International Bank for

Reconstruction and Development), was signed in Karachi on September 19, 1960 by

then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and President of Pakistan Ayub Khan.

While the World Bank is a signatory to the Treaty for certain specified

purposes, it is not a guarantor of the Treaty. The Treaty allows control over

the three ‘eastern’ rivers of the Indus river system— the Ravi, Beas and Sutlej

—to India and control the three ‘western’ rivers — the Indus, Jhelum and Chenab — to Pakistan. The treaty

stipulates that while water from the rivers Indus, Jhelum and Chenab will be

used exclusively by Pakistan, water from the rivers Ravi, Beas and Sutlej will

be used by India. The IWT also stipulates that either party (country) must

notify the other of plans to construct any engineering works which would affect

the other party and to provide data about such works.

While India cannot store any

water from these rivers or stop them from flowing to Pakistan, it can construct

hydroelectric power projects over these rivers, but has to allow a free flow of

water. India can however go in for ‘pondage’, i.e., water being held behind a

dam for a short time (as it flows into turbines to generate electricity) but

even this is limited. Pondage is very different from storing Indus water, say,

for major irrigation projects. Additionally, India must share designs of

projects for irrigation and hydro power generation, water flow data and a host

of other information with Pakistan.

The IWT, which is largely regarded

as one of the success stories of water diplomacy between two neighboring

nations, whose relations are often petulant, is essentially an arrangement to

implement a fair distribution of a critical natural resource – water – between

India and Pakistan. The Treaty also provides for mechanisms to resolve disputes

over water sharing.

The treaty was a result of

Pakistani apprehension that, since the source rivers of the Indus basin were in

India (in the state of J&K), India could therefore potentially create

droughts and famines in Pakistan, especially at times of war, by stopping or

diverting away water from downstream Indus and its sister rivers. The treaty, signed

more than five decades ago has remained in effect even during the wars between

India and Pakistan—in 1965, 1971 and 1999. However, the Pakistani State, in

spite of the Treaty being in place for over five decades now, has always

remained in perpetual apprehension of the possibility of India repealing the

Treaty, and the consequences of the same in Pakistani economy. That there is

solid ground for this apprehension emanates from the ever worsening water

crisis in Pakistani.

Pakistan’s Water Crisis

In a report published

in 2013, the Asian Development Bank had described Pakistan as one of the most ‘water-stressed

countries in the world, with a water availability of 1,000 cubic meters per

person per year, a fivefold drop since its independence in 1947, which is about

the same level as drought-stricken Ethiopia!

Total annual per capita actual

renewable water resources in

Pakistan in 2014 had been estimated at 1,306 cubic meters. The graphic below illustrates the depletion in per capita renewable water resources in

Pakistan during 1962-2014.

A country with annual

water availability below 1,000 cubic metres per capita is designated as a

water-scarce country. Pakistan is expected to become water-scarce by 2035,

however based on current trends it is likely

that per capita water availability will decline to around 800 cubic

metres by 2025,

making Pakistan a water scarce country.

According to the Pakistan Council

of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR), the country has an estimated population

of 187 million with an annual growth rate of 1.57 %. By the year 2050, Pakistan’s

population is likely to double and become 63.7% urban. This will definitely put

tremendous pressure on water supply for households, industry and agriculture.

Pakistan has been facing a number of water related challenges. A few of these

challenges include:

- Water

shortage

- Inadequate

water harvesting and storage facilities (only 10% of the average annual flow)

- Reduction

in storage capacities of the existing reservoirs due to sedimentation

- Low

system efficiency

- Conventional

methods of irrigation - unleveled basins, improper size of furrows

- Low

land and water productivity

- Non-existent

national water policy

- Water

logging and salinity

- Unmanaged dry lands

- Lack

of monitoring infrastructure for glaciers and trans-boundary inflows.

The aforementioned problems get compounded by the

apprehension of the Pakistani think tank that any action –intentional or

unintentional– on the part of the Indian authorities to control the water

supply of the Indus system can lead to famines and droughts in Pakistan.

Pakistan has also had limited success with harnessing its

water resources towards developing hydro power generation capacity in order to

meet its ever burgeoning energy demands. As on date Pakistan's energy

generating capacity is 24,830 MW; the country currently faces energy shortfalls

of over 4,500MW on a regular basis with routine power cuts of up to 5 hours per

day, which has shed an estimated 2–2.5% off its annual gross domestic product (GDP).

At the Crux of the Matter

At the root of the Kashmir crisis

lies the Indus river system. Pakistan, being largely an agrarian economy,

depends heavily on the Indus waters for agriculture, employment, and a

significant portion of its GDP. It is widely acknowledged that the Indus river

provides Pakistan with:

- 90% of its freshwater for agriculture

- 50% of the country's employment

- 25% of its GDP

It is no wonder therefore that the

inhabitants of Pakistan affectionately refer to the Indus as

‘the water of life.’

Tumorous population growth in

both India and Pakistan has led to increased strain on the river for power

generation and drastic measures on the part of India to secure sufficient

hydropower to prevent sudden power outages. Pakistan for quite some time has

been accusing India of stealing water from ‘the water of life.’ Pakistan

alleges that India is ‘stealing’ its river waters, by violating the IWT.

Pakistan’s allegations, at the moment, centre on the Nimmo-Bazgo and Chutak

hydroelectric power projects over the Indus river in J&K. The allegation is

that by going ahead with these projects, India is trying to divert river waters

that rightly belong to Pakistan.

Many reports in recent times have

highlighted that India too is a water stressed country and its water disputes

(both intra and inter country) are bound to grow as Indian authorities strive

to manage water for India’s huge population. Renewable internal freshwater

resources in the country (in terms of cubic meters per capita) has come down

from 3,089 (in 1962) to 1,116 (in 2014).

In comparison, the neighbouring nation of Myanmar has a per capita renewable

internal freshwater resources 18,770 cubic meters in 2014. Even Bhutan with per

capita renewable internal freshwater resources of 101,960 cubic meters lead the

south Asian nation in 2014.

The face-off between Punjab and

Haryana over sharing of Satluj-Yamuna water and as well between Tamil Nadu and

Karnataka over sharing of Cauvery water as the has put the spotlight on brewing

confrontations between states across India over access to water. Even the newly

formed state of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh too have locked horns over

numerous water projects. A recent study pegs that 80% of India’s 1.25 billion

population faces severe water scarcity for at least a month every year and 180

million Indians face severe water scarcity all year round. No, doubt India is

increasingly looking at harnessing hydropower to find sustainable answers to

its water and energy crisis.

What if the IWT were abrogated?

The Indus Water Treaty is one of

the best examples of cooperation between countries as the most logical response

to trans-boundary water management issues. India has not disturbed the flow of

water to Pakistan even during wars, acts of terrorism and other such conflicts

that have bedeviled relations between the two neighbours. The Treaty gives up

to 80 % of the water from six rivers — the Beas, Ravi, Sutlej, Indus, Chenab

and Jhelum — shared by the two countries to Pakistan, and has, therefore, been seen

in India as being ‘too soft’ on Pakistan.

Sadly, this treaty between India

and Pakistan, which has survived three wars and numerous lows in India-Pakistan

relations, stands seriously threatened today. The Indian Government,

understandably is under tremendous public pressure to take material actions

against Pakistan, to rein in terrorism stemming from the Pakistani soil against

India, as a repercussion to the gruesome killing of eighteen soldiers of the

Indian Army in the Uri terror attack on September 18, 2016 (in J&K).

An insightful

analysis (as illustrated in the figure underneath), undertaken by Data-Analyst

Adipta Datta (an alumnus of ICFAI Business School, Kolkata) based on the

comments made on social media pages (such as Facebook) of popular traditional

media such as NDTV, Firstpost and others immediately in the aftermath of the

URI incident and related to the incident, finds a significant percentage (63%) of

the commentators viewing the incident with skepticism, which Datta refers to as

negative sentiments associated with the incident.

Such negative sentiments stem

from such comments wherein the post owners (commentators) have not related

positively with the URI attacks i.e., they did not quite believe in the

authenticity of the attack, to that extent that many of them felt that the

attacks could have even been faked by the Indian State, in order to draw

attention of the international community to the Kashmir issue/Pakistan. However,

such sentiments cannot be seen as representative of the Indian population, as

the reach of English news channel is around 12 million as against the reach of

Hindi news channels which is about eight times that of the English news

channels.

In what was a much looked up to

high-level meeting chaired by the Indian Prime Minister with senior Government

officials on September 26, 2016 to review Indus Waters treaty, which had also

fueled speculations that the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government may

ultimately seek to alter or scrap the provisions of the 1960 pact with

Pakistan, it was decided that India will now expedite the construction of three

dams on River Chenab.

It is being widely perceived in

India that such a pressure tactic (of altering or scrapping the provisions of

the Treaty) is likely to compel Pakistan to crackdown on non-state and state

actors acting operating on its soil against India. This is not to say that

there are no pockets of cogent thought in India that question the astuteness

and practicality of this approach to confronting Pakistan. In this connection,

an editorial, published way back in 1998, in The Statesman, a venerable

English-language daily published in Kolkata is perhaps still relevant and is

worth quoting at some length:

“India, the bigger and

arguably the more mature of the two (countries), must take the lead (in heading

off an arms race). And no lead is better than a grand policy on Kashmir...India

should respond to Pakistan’s tests and the possibility of escalating tensions

by making a unilateral posture on Kashmir. It can announce that the government

will exhume the nearly five decades old United Nations proposal to hold a

referendum on the question of the valley’s (Jammu & Kashmir) territorial

loyalty.This will seem

preposterous to the BJP, indeed to many Indians. But an astute political party

– BJP has shown it can be one – does not remain a prisoner of conventional

wisdom. More, a referendum on and in Kashmir, internationally supervised, will

again put India in a different league from one defined by sub-continental

squabbles – a status the BJP thinks the country deserves. The ‘worst’

possibility is that Kashmir may not choose to remain with India. Is that too

bad a prospect compared to the price India pays in blood, money, and a general

marring of reputation when the troops ‘occasionally’ misbehave? A Kashmir

referendum will also blunt global condemnation of the subcontinent as a mad

hatter area full of nuke-wielding hot-heads. As well as forcing Pakistan to

drop its belligerence, both verbal and clandestine. These are benefits that can

be grabbed only by a government with vision and courage.”

Earlier on September 22 2016 India

signalled that it could

revisit the IWT on sharing of the waters of the river Indus, against the

background of Pakistani State ignoring Indian concerns over its continued

support to terrorism. However, a unilateral abrogation of the Indus Water

Treaty (IWT) on India’s part is likely to attract criticism from world powers. India

definitely runs the risk of alienating the World Bank if it abrogates the

treaty, especially the US, the UK, Canada, (then) West Germany, Australia and

New Zealand underwrote the facilitation of the treaty by contributing $1

billion (at 1959 rates) and virtually bribed Pakistan by giving it $315 million

to enter into negotiations with India. Besides, China will be under no

obligation to allow water from the Indus or Sutlej rivers to flow into India. Indus,

which is covered by the IWT, originates in China, the fountainhead of this

river basin lying in China.

China being not a party to the

Indus Water Treaty may decide to divert water from the Indus river in the

absence of any international treaty governing the management of this precious

resource, India will be deprived of 36 % of the river's entire flow. Countless

canals from which cities and towns draw water for daily use would dry up,

causing urban and semi-urban distress. If China also decides to shut off water

from Tibet that feeds the Sutlej river, huge swathes of northern India would be

plunged into darkness and deprived of power. Water from the Sutlej flows into

the Bhakra dam, the Karcham Wangtoo hydro-electric project and the Nathpa

Jhakri dam which together generate at least 3,600 megawatts of electricity that

lights up large parts of Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh,

Chandigarh and Delhi. Besides, stopping water supplies to Pakistan after any

abrogation of the 1960 Treaty is likely to flood extensive areas of Jammu and

Kashmir and Punjab.

There is also the possibility

that China could utilize the opportunity, in the event of IWT being abrogated

by the Indian Government, to divert water from the Brahmaputra river, which

forms the lifeline of India’s north eastern region.

Arguments & Counter Arguments

Arguments and counter

arguments, as well as allegations and counter allegations have led the two

countries nowhere, except that the such instances have only led to unnecessary

wars, and mistrust between two very culturally close set of populations. For

instance, while Pakistan’s allegation that Indian Government's plans to divert

the course of the Kishenganga river (a tributary of the Indus) to build a

330-megawatt hydroelectric power project will reduce the river’s flow by a

third in the winter. That would make it unfeasible for Pakistan to move ahead

with its own plans for a hydroelectric dam downstream.

Essentially, both India and

Pakistan were fighting over control of Kashmir since independence in 1947,

where several Indus tributaries begin, because control of Kashmir means gaining

the much needed control of the waters of the Indus system, until the IWT was

signed between the two countries in 1960. Yet Pakistan's rows with India have

intensified as its water situation has worsened over the years. On the

contrary, observers in India say Pakistan is simply looking for a scapegoat as

it struggles to manage its internal water politics – citing instances of the

especially arid Pakistani province of Sindh, blaming the prosperous upstream Pakistani

province of Punjab for consuming too much of Indus waters. But off-late even farmers

from the Punjab province have been complaining that agricultural yields and

incomes have dropped by a third in the past five years because of water

shortages. In the past, canals used to supply water for irrigation year-round.

They are now empty for about four months each year, forces farmers and villagers

to pump groundwater, which is fast turning brackish and causing diseases like

hepatitis.

Pakistan's rows with India have

intensified as its water situation has worsened over the years. In 2005

Pakistan had raised issues with the Baglihar dam, an Indian power project on

the Chenab river alleging that the dam

would store too much water upstream and reduce downstream flow to Pakistan. Subsequently

in 2007 the World Bank mediated by appointing an independent expert, who ruled

that India had to make minor modifications to the dam, such as lowering its height.

Pakistan now contends that the dam, which began operations in 2008, is reducing

the flow of the Chenab below levels stipulated in the treaty. India denies such

an allegation. The Indian projects that Pakistan believes are draining its

water resources are primarily on Indus tributaries in Kashmir.

B.G. Verghese, a veteran

journalist who has studied water issues closely and is a visiting professor at

the Center for Policy Research, a New Delhi based think tank, says,

"They're saying, 'We

must liberate Kashmir to save our water.'"

Case

for an Alternate Dispute Resolution for Kashmir

It is quite understandable why the popular

Pakistani conscience revolves around Kashmir being the jugular vein of

Pakistan, because without Kashmir and its rivers, its dream of economic

independence is likely to remain utopian. This explains, why in spite of being supportive

of the Kashmiris ‘right of self-determination,’ Pakistan has never accepted the

third option as a possible outcome - a third option being Independent, and

allegiance to neither India nor Pakistan. The same logic is also perhaps true,

as to why India remains so steadfast on not conducting the much awaited

promised plebiscite.

The predominant reason why India and Pakistan have

been bickering over the control of Kashmir is because that is where several of

the Indus tributaries begin. Needless to say, that there is an immediate need

that, both India and Pakistan develop a transparent,

participatory, democratic, and rule-based management – with integrated regional

approach – of waters of the Indus system.

It needs to be appreciated by the

Indian think tank that success of the region (south Asia) is critical to

India's long term prosperity. Taking everybody along in the region, instead of

being the 'Big Brother' in the region, has to be Indian strategy for ensuring

nation’s long term sustainability.

It is the need of the hour that

both nations realize there are absolutely no brownie points to be acquired by

keeping control over a common natural resource – water of Indus system – which

is for public good for the riparian communities – upstream as well as

downstream. Any developmental activities being carried out on the upstream of a

river system, which has been conceived for good for the upstream communities and

without any regard to the downstream communities, is bound to impact

devastatingly the downstream communities. This in the long run will only create

animosity and mistrust between the communities; which will eventually lead to

nuclear polarization of the sub-continent – thereby putting lives of billions

of people in the region at stake.

Governments and States have no right to act so irresponsible.

It will therefore require policy

makers, researchers, advocacy groups, development professionals and civil society

groups from both nations to come together on one platform and build mutual

awareness and understanding of the common water resource challenges and put

pressure on their respective Governments to works towards achieving sustainable

development in all its three dimensions – social uplift, economic development

and environmental conservation.

Beyond Kashmir

India, owing to its demographic

size and nuclear arsenal, sees its role as a potential counterweight to China

on the global platform, and expects that this would translate into economic

importance and the much coveted seat on the United Nations Security Council.

However, by and large, global strategic currents still continue to bypass

India.

India, perhaps instead of looking

at China as a potential aggressor, needed to have attempted at understanding

China’s global trade and business aspirations and interests, and in the process

could have seen itself as a major ally.

The Indian policy makers need to understand that the principal measure

of power in the 21st century is connectivity, specifically to global

infrastructure networks, trade flows, capital markets and the digital economy; and

by that measure China is already a dominant global power. China, as of today,

ranks as the top trade partner of more than 120 countries in the world, which

is double the number for the US (56), and far higher than for India (just one).

Many decades back, when the United States was by far the dominant economic

super power, India was far from anything that could have been remotely termed

as ‘being on friendly terms’ with the United States. Even now, India views

China with great mistrust. In fact, India not mistrusts China but is also

equally sceptic about having a trustworthy relationship with its major

neighbours – Pakistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar and Sri Lanka. It is sad, all these

nations have had a shared past for millennia of growth, prosperity, trade and

culture, and even very recent shared experiences of colonial hardships. People

to people connect, owing to shared culture across Indian subcontinent still

remains strong, and yet, India has miserably failed to convert such powerful

connects into formal avenues for economic growth and prosperity.

It needs to be understood with

immediate effect, where India has been failing, w.r.t cultivating a mutually

beneficial relationship with neighbors, China is having great success at that –

creating and forging alliances (especially in the Indian ocean rim) for the

future.

The China–Pakistan

Economic Corridor often referred to by the acronym CPEC is one such example.

The CPEC, is a collection of projects currently under construction at a cost of

$46 billion,

intended at rapidly expanding and upgrading Pakistani infrastructure as well as

deepen and broaden economic ties between Pakistan and China. Infrastructure

projects under the tutelage of CPEC is expected to span the length and breadth

of Pakistan, and will eventually link the city of Gwadar in southwestern

Pakistan to China's northwestern autonomous region of Xinjiang via a vast

network of highways and railways. Over $33 billion worth of energy

infrastructure are to be constructed by private consortia to help alleviate

Pakistan's chronic energy shortages, which regularly amount to over 4,500MW.

Over 10,400MW of energy generating capacity is to be developed between 2018 and

2020 as part of the corridor. CPEC will be a strategic game changer in for

Pakistan’s economy and also in the south-Asian region. The Government of India

instead of seeking benefits from this regards portions of the CPEC project

negatively as these pass through the Pakistani-administered side of Kashmir, a

territory that India disputes.

In response to India’s objection

to the corridor, the Chinese Government has stated that the CPEC which passes through

Pakistan occupied Kashmir, is not designed to target India or take Pakistan’s

side on the Kashmir dispute; instead is certainly a platform to further

strengthen China-Pak cooperation. The Chinese position on the CPEC is that the

corridor also benefits the region and is likely to positively contribute to the

peaceful and steady development of the south Asian region and that many

countries have already expressed their willingness to be a part of the project.

It remains open to speculation

whether India will choose to oppose the CPEC or seek an active role for itself

in the integrated regional development, that the CPEC is expected to

facilitate. Even as India seeks to improve trade relations with countries along

the Indian Ocean periphery, it must focus on improving its trade balance with

China through higher value-added exports, and at the same time also on attracting

more and more foreign direct investment from China into power, transportation

and other key sectors – sectors that will lead to – social uplift and economic

development in India.

To not connect to India’s

neighbors – China, Pakistan, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and beyond is to

further cede strategic ground along the 21st century’s new trade routes.

Disclaimer / Caveat: The article reflects the views of the writer alone and does not seek to offend any community within or outside India. Its purpose is to purely encourage discussion.

(

This post is not copyrighted and may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution of source)